Our results are based on two forms of explanation proposed in the literature for defeasible reasoning which we refer to as weak and strong justification. Before discussing our results, we first introduce these forms of defeasible explanation.

Weak Justification

A simple way to define explanation for Rational Closure defeasible entailment is to make use of classical justification on the statements that are not 'thrown out' when reasoning. Consider

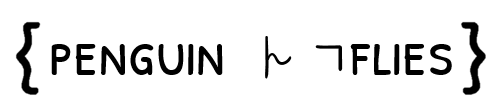

for example the statements that were remaining when reasoning about penguins flying in our discussion of Rational Closure:

While we would check for classical entailment on the remaining statements when checking for defeasible entailment, here we use classical justification on the remaining

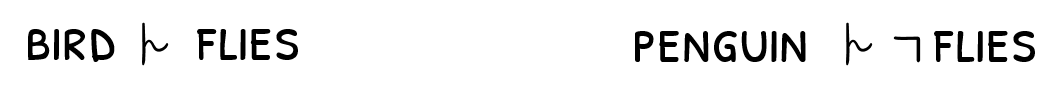

statements to obtain a form of defeasible explanation. According to this definition, we would for example justify the entailment that ‘penguins typically do not fly’ using only the relevant statement:

While we would check for classical entailment on the remaining statements when checking for defeasible entailment, here we use classical justification on the remaining

statements to obtain a form of defeasible explanation. According to this definition, we would for example justify the entailment that ‘penguins typically do not fly’ using only the relevant statement:

We refer to this form of defeasible explanation as weak justification to distinguish from other forms of defeasible explanation.

Weak justification seems to be a fairly intuitive form of defeasible explanation and closely matches the reasoning process for Rational Closure.

We refer to this form of defeasible explanation as weak justification to distinguish from other forms of defeasible explanation.

Weak justification seems to be a fairly intuitive form of defeasible explanation and closely matches the reasoning process for Rational Closure.

Strong Justification

While weak justification seems to be a practical form of defeasible explanation, there is some evidence that it may not

capture all aspects of the reasoning process. Intuitively, while weak justifications seems to select the statements that are used

to obtain the conclusion, it does not necessarily provide context as to why the statements selected are the most applicable. While in the example

above the strong justifications are no different than the weak justifications, other examples illustrate the distinction.

Consider what happens if we try use the information we previously modeled to reason about an entity directly specified to be both a penguin and a bird (hereafter referred to as a penguin–bird):

Suppose we want to decide whether ‘penguin–birds typically fly’. The fact that penguins are an exceptional kind of bird is critical here

as it dictates which one of these two rules in the knowledge base is actually applicable in this circumstance:

Suppose we want to decide whether ‘penguin–birds typically fly’. The fact that penguins are an exceptional kind of bird is critical here

as it dictates which one of these two rules in the knowledge base is actually applicable in this circumstance:

Of course, it is the latter rule that is applicable as shown in our comic, and indeed this is the rule that applies according to Rational Closure entailment.

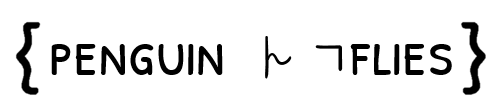

The weak justification here is identical to the one we had when reasoning about penguins in our first example:

Of course, it is the latter rule that is applicable as shown in our comic, and indeed this is the rule that applies according to Rational Closure entailment.

The weak justification here is identical to the one we had when reasoning about penguins in our first example:

Strong justification is a distinct notion of defeasible explanation defined based on the idea that no matter what information we add from our knowledge base, the strong justification still defeasibly entails the statement. The strong justification, unlike the weak justification, includes the information that ‘penguins are birds’ and therefore the information that penguins are an exceptional kind of bird:

Strong justification is a distinct notion of defeasible explanation defined based on the idea that no matter what information we add from our knowledge base, the strong justification still defeasibly entails the statement. The strong justification, unlike the weak justification, includes the information that ‘penguins are birds’ and therefore the information that penguins are an exceptional kind of bird:

This illustrates how strong justifications may be intuitively more comprehensive than weak justifications, although we do find that they are more difficult to compute and have some undesirable sensitivities to syntax.

This illustrates how strong justifications may be intuitively more comprehensive than weak justifications, although we do find that they are more difficult to compute and have some undesirable sensitivities to syntax.

Results

- Adapts weak justification, previously only explored for Rational Closure, to Relevant Closure.

- Gives a series of intuitive properties expected for sensible defeasible explanation and shows that weak justification satisfies these properties.

- Adapts weak justification to Lexicographic Closure.

- Proposes an algorithm for the evaluation of strong justifications for KLM-style defeasible reasoning for Rational Closure.

- Proposes an alternative general definition for defeasible explanation in the context of an extension of the KLM framework.